library(jpeg) # For reading JPEG images

library(tibble) # For creating data frames

library(dplyr) # For data manipulation

library(ggplot2) # For plotting

# Create a dummy image for demonstration if actual image is not present

# In a real scenario, you'd replace this with your actual image path

if (!file.exists("images/JODAVID.jpg")) {

message("images/JODAVID.jpg not found. Creating a dummy image for demonstration.")

# Create a simple image data (e.g., 50x50, 3 channels)

dummy_image_data <- array(runif(50*50*3), dim = c(50, 50, 3))

# Create the directory if it doesn't exist

if (!dir.exists("Figures")) {

dir.create("Figures")

}

# Save a simple JPEG image

writeJPEG(dummy_image_data, "images/JODAVID.jpg")

}

# Read the image

imagem <- readJPEG("images/JODAVID.jpg")

# Organize the image into a data frame (long format)

# Each row represents a pixel with its (X,Y) coordinates and RGB values

imagemRGB <- tibble(

X = rep(1:dim(imagem)[2], each = dim(imagem)[1]),

Y = rep(dim(imagem)[1]:1, dim(imagem)[2]), # Y-axis inverted for plotting

R = as.vector(imagem[,,1]),

G = as.vector(imagem[,,2]),

B = as.vector(imagem[,,3])

)Statistical Machine Learning

Clustering Methods

UFPE

The Challenge of

Unsupervised Learning

- Until now, we have been concerned supervised learning methods such as regression and classification.

- In the supervised setting, we typically have:

- A set of \(p\) features \(\mathbf{x}_1 = \{X_{11}, X_{12}, \ldots, X_{1p}\}\).

- A response \(Y\).

- All measured on \(n\) observations.

- The goal is to predict \(Y\) using \(X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_p\).

The Challenge of

Unsupervised Learning

- Unsupervised learning focuses on settings where we only have a set of features \(\mathbf{x}_i = \{X_{i1}, X_{i2}, \ldots, X_{ip}\}\) measured on \(n\) observations (\(i = 1, \ldots, n\)).

- We are not interested in prediction, because we do not have an associated response variable \(Y\).

- Rather, the goal is to discover interesting things about the measurements on \(\mathbf{x}_i = \{X_{i1}, X_{i2}, \ldots, X_{ip}\}\).

The Challenge of

Unsupervised Learning

- Key questions in Unsupervised Learning:

- Is there an informative way to visualize the data?

- Can we discover subgroups among the variables or among the observations?

- Unsupervised learning refers to a diverse set of techniques for answering questions such as these.

- This chapter will focus on two particular types:

- Clustering: Discovering unknown subgroups in data.

- Principal Components Analysis (PCA): Data visualization or pre-processing.

The Challenge of

Unsupervised Learning: Difficulties

- Unsupervised learning is often much more challenging than supervised learning.

- The exercise tends to be more subjective, with no simple goal like prediction.

- Often performed as part of an exploratory data analysis.

- Hard to assess results: No universally accepted mechanism for cross-validation or validating results on an independent data set.

- Why? In supervised learning, we can check predictions against the known response. In unsupervised learning, we don’t know the “true answer”.

The Challenge of

Unsupervised Learning: Applications

- Despite the challenges, unsupervised learning is of growing importance.

- Cancer research: Identify subgroups among breast cancer samples or genes for better disease understanding.

- Online shopping: Identify groups of shoppers with similar browsing/purchase histories, recommend items.

- Search engines: Display tailored search results based on click histories of similar individuals.

- These and many more statistical learning tasks can be performed via unsupervised learning techniques.

What is Clustering?

- Clustering refers to a very broad set of techniques for finding subgroups, or clusters, in a data set.

- When we cluster the observations of a data set, we seek to partition them into distinct groups so that:

- Observations within each group are quite similar to each other.

- Observations in different groups are quite different from each other.

- The definition of “similar” or “different” is often a domain-specific consideration based on knowledge of the data.

Clustering vs. PCA

- Both clustering and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) seek to simplify the data via a small number of summaries.

- However, their mechanisms are different:

- PCA looks to find a low-dimensional representation of the observations that explain a good fraction of the variance.

- Clustering looks to find homogeneous subgroups among the observations.

Applications of Clustering

- Biology / Medicine:

- Identifying unknown subtypes of breast cancer from tissue samples with gene expression measurements.

- Discovering structure (distinct clusters) in a data set without prior labels.

- Marketing:

- Performing market segmentation by identifying subgroups of people who might be more receptive to a particular form of advertising or more likely to purchase a product.

K-Means Clustering

Introduction

- K-Means clustering is a simple and elegant approach for partitioning a data set into \(K\) distinct, non-overlapping clusters.

- To perform K-Means clustering, we must first specify the desired number of clusters \(K\).

- The K-Means algorithm then assigns each observation to exactly one of the \(K\) clusters.

K-Means Clustering

Objective Function

- Let \(C_1, \ldots, C_K\) denote sets containing the indices of the observations in each cluster.

- These sets satisfy two properties:

- \(C_1 \cup C_2 \cup \dots \cup C_K = \{1, \ldots, n\}\). Each observation belongs to at least one cluster.

- \(C_k \cap C_{k'} = \emptyset\) for all \(k \neq k'\). Clusters are non-overlapping.

- The idea behind K-Means clustering is that a good clustering is one for which the within-cluster variation is as small as possible.

- We want to solve the problem: \[ \min_{C_1, \ldots, C_K} \sum_{k=1}^K W(C_k) \] where \(W(C_k)\) is a measure of the amount by which observations within cluster \(C_k\) differ from each other.

K-Means Clustering

Within-Cluster Variation

- The most common choice for within-cluster variation is based on squared Euclidean distance: \[ W(C_k) = \frac{1}{|C_k|} \sum_{i,i' \in C_k} \sum_{j=1}^p (x_{ij} - x_{i'j})^2 \] where \(|C_k|\) denotes the number of observations in the \(k\)-th cluster.

- This formula represents the sum of all pairwise squared Euclidean distances between observations in the \(k\)-th cluster, divided by the total number of observations in that cluster.

K-Means Clustering

Optimization Problem

- Combining the objective function with the definition of within-cluster variation, the K-Means optimization problem is: \[ \min_{C_1, \ldots, C_K} \sum_{k=1}^K \frac{1}{|C_k|} \sum_{i,i' \in C_k} \sum_{j=1}^p (x_{ij} - x_{i'j})^2 \]

- This is a very difficult problem to solve precisely due to the huge number of possible partitions.

The K-Means Algorithm

Steps

- A simple iterative algorithm is used to find a local optimum for the K-Means optimization problem.

Random Assignment: Randomly assign a number, from 1 to \(K\), to each of the observations. These serve as initial cluster assignments.

Iterate until cluster assignments stop changing:

- Compute Centroids: For each of the \(K\) clusters, compute the cluster centroid. The \(k\)-th cluster centroid is the vector of the \(p\) feature means for the observations in the \(k\)-th cluster. \[ \bar{x}_{kj} = \frac{1}{|C_k|} \sum_{i \in C_k} x_{ij} \]

- Assign Observations: Assign each observation to the cluster whose centroid is closest (using Euclidean distance).

The K-Means Algorithm

Why it Works

- The algorithm is guaranteed to decrease the value of the objective function at each step.

- The identity \(\frac{1}{|C_k|} \sum_{i,i' \in C_k} \sum_{j=1}^p (x_{ij} - x_{i'j})^2 = 2 \sum_{i \in C_k} \sum_{j=1}^p (x_{ij} - \bar{x}_{kj})^2\) is illuminating.

- Step 2(a) computes cluster means that minimize the sum of squared deviations for fixed assignments.

- Step 2(b) reallocates observations, which can only improve the objective for fixed centroids.

- The algorithm stops when the cluster assignments no longer change, indicating a local optimum has been reached.

The K-Means Algorithm

Multiple Runs

- Since the K-Means algorithm finds a local rather than a global optimum, the results depend on the initial (random) cluster assignment.

- Therefore, it is important to run the algorithm multiple times from different random initial configurations.

- Then, one selects the best solution, i.e., the one for which the objective function is smallest.

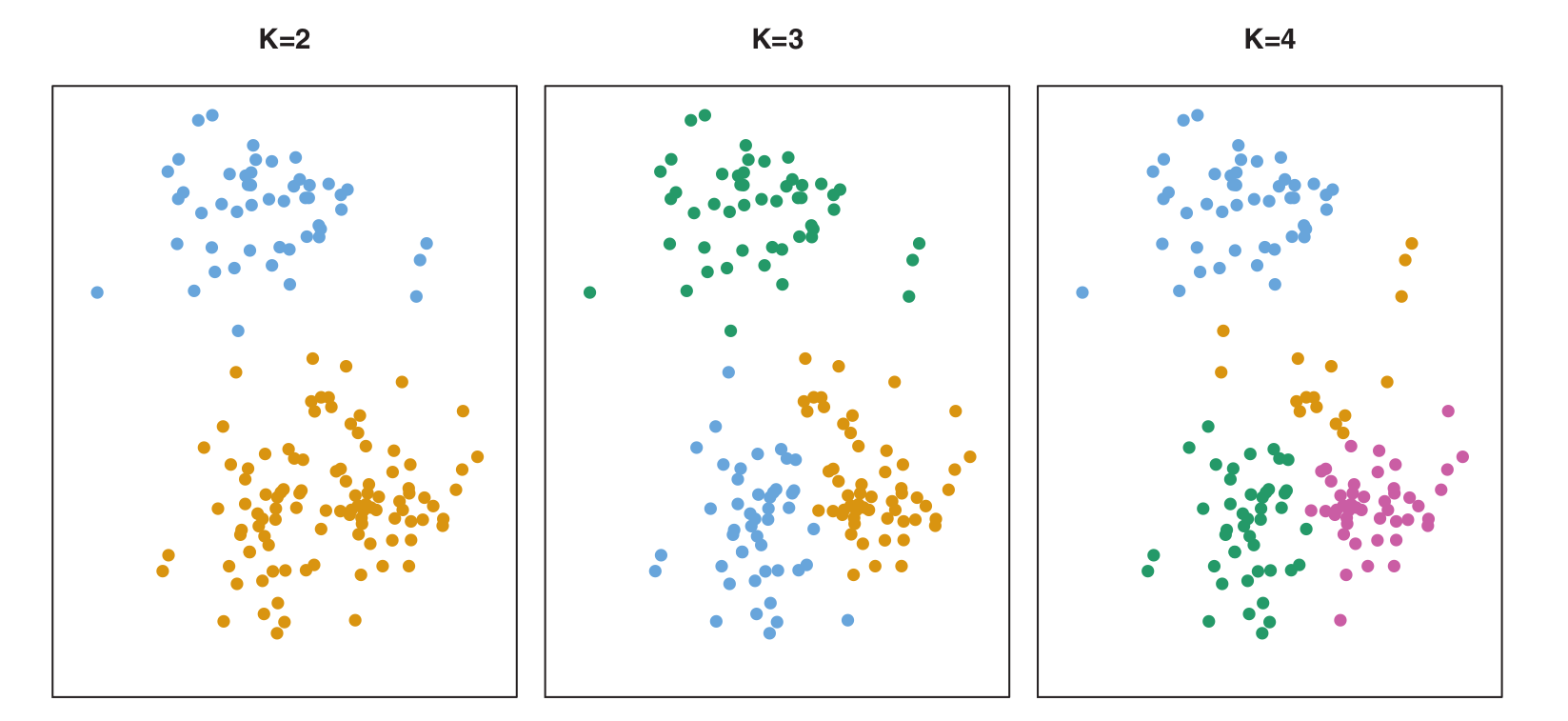

K-Means Visualization

Initial Data and Progression

- Let’s visualize the K-Means algorithm with a simulated 2D dataset (\(n=150\)).

Figure (K=2, K=3, K=4): Shows how the clusters are formed for different values of \(K\).

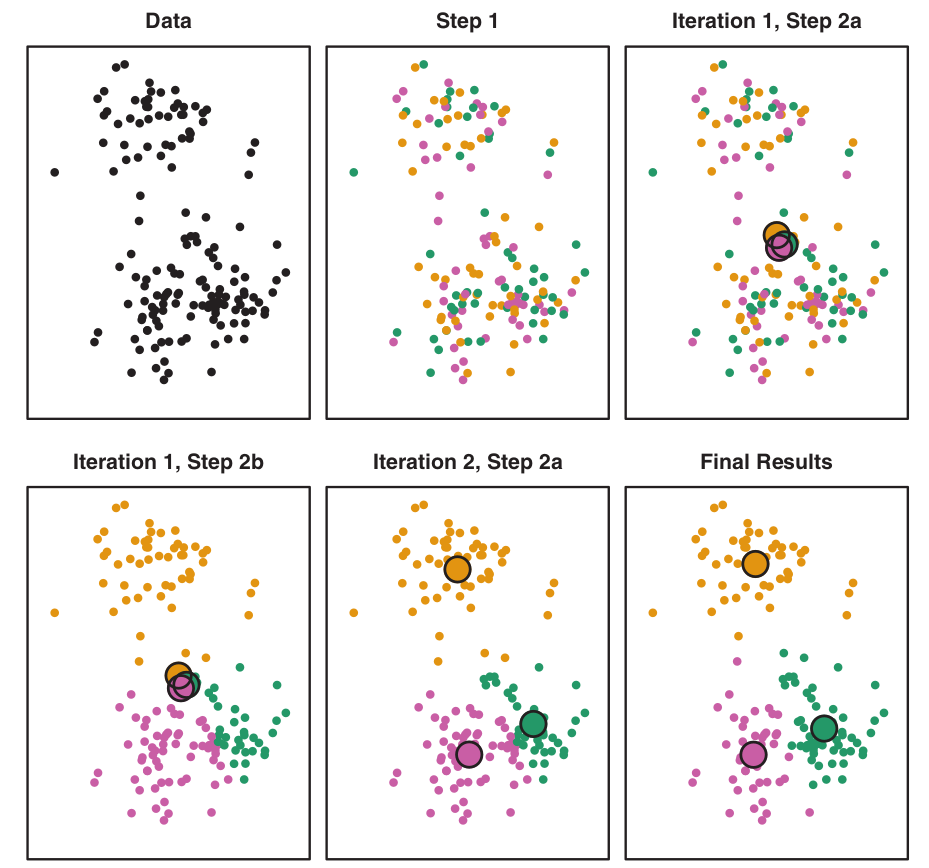

K-Means Visualization

Algorithm Steps (K=3)

Figure: Illustrates the progression of K-Means algorithm for \(K=3\):

- Top left: Observations.

- Top center: Initial random assignment.

- Top right: Centroids computed.

- Bottom left: Observations reassigned.

- Bottom center: New centroids.

- Bottom right: Final result after 10 iterations.

K-Means Visualization

Multiple Initializations

Figure: K-Means clustering performed six times with different random initial assignments for \(K=3\).

- Values above each plot show the objective function.

- Multiple local optima are obtained. The best solution (lowest objective, \(235.8\)) provides better separation.

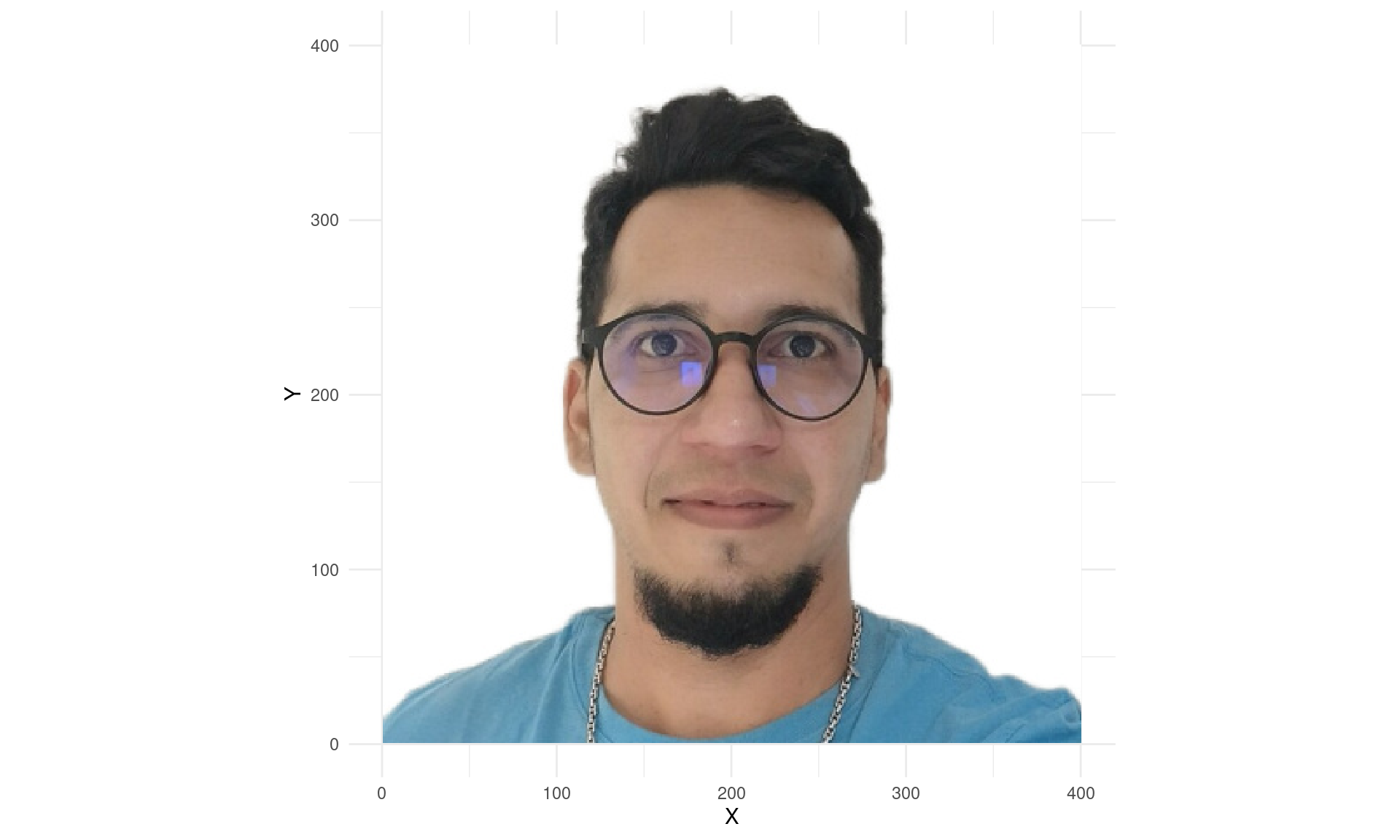

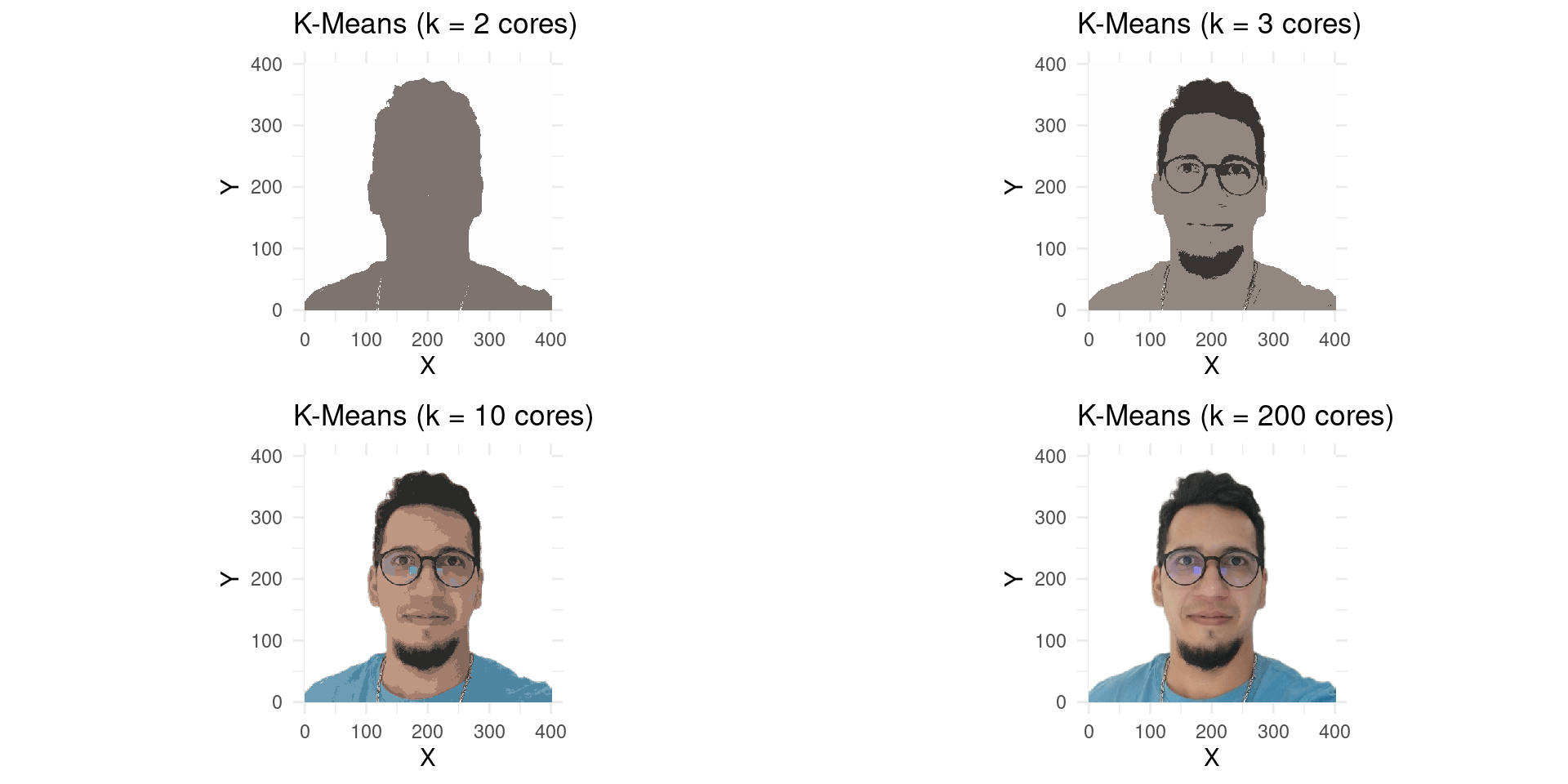

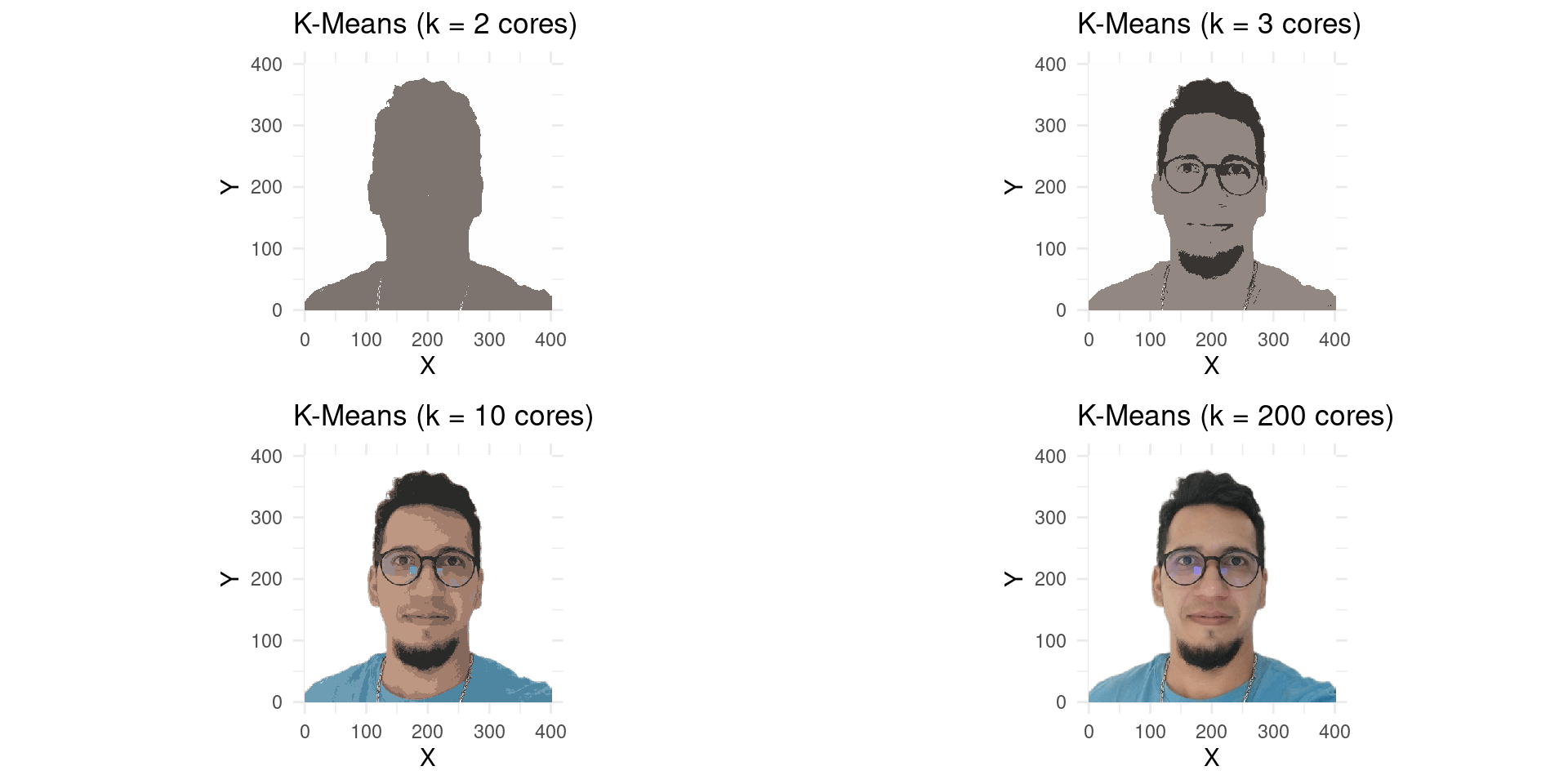

R Example: K-Means on Image Pixels

Goal

- We will use K-Means to cluster the pixels of an image based on their colors (R, G, B values).

- Each pixel will then be represented by its cluster’s centroid.

- The number of clusters (\(K\)) will correspond to the number of colors in the resulting image.

R Example: K-Means on Image Pixels

Code - Data Preparation

R Example: K-Means on Image Pixels

Code - Data Preparation

R Example: K-Means on Image Pixels

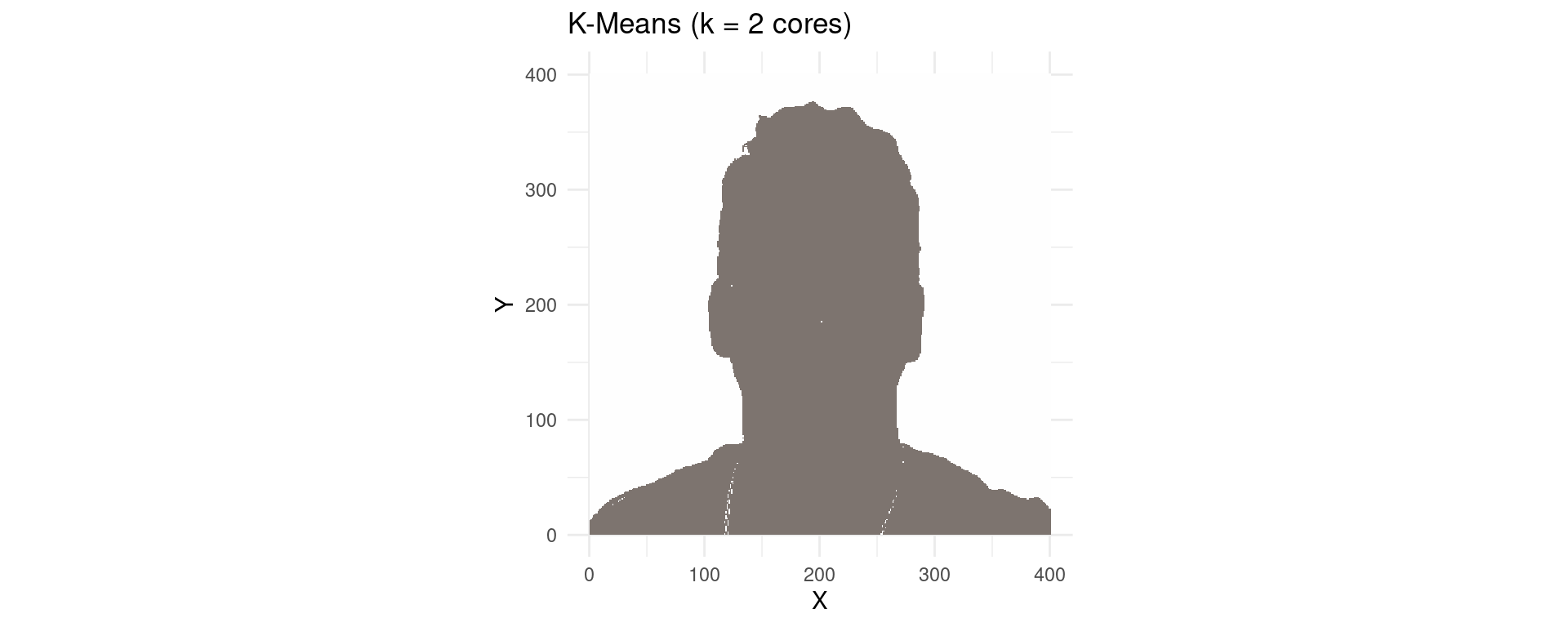

Code - K-Means Application

# Specify the number of clusters (colors)

k <- 2

# Apply K-Means clustering

# We cluster the RGB values, ignoring X and Y coordinates for clustering logic

kMeans_result_k2 <- kmeans(imagemRGB[, c("R", "G", "B")], centers = k)

# Add the cluster assignment and new color (centroid color) to the data frame

imagemRGB_k2 <- imagemRGB |>

mutate(cluster = kMeans_result_k2$cluster) |>

mutate(kColours = rgb(

kMeans_result_k2$centers[cluster, "R"],

kMeans_result_k2$centers[cluster, "G"],

kMeans_result_k2$centers[cluster, "B"]

))

# Plot the image with k=2 colors

p1 <- ggplot(imagemRGB_k2, aes(x = X, y = Y, color = I(kColours))) +

geom_point(show.legend = FALSE, shape = 15, size = 0.1) + # Use shape 15 for square pixels

labs(title = paste("K-Means (k =", k, "cores)")) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(aspect.ratio = dim(imagem)[1]/dim(imagem)[2]) + # Maintain aspect ratio

scale_color_identity() # Use exact colors from kColoursR Example: K-Means on Image Pixels

K-Means with K=2 Colors

R Example: K-Means on Image Pixels

More Colors!

- Let’s try with more colors, say \(K=3\), \(K=10\), and \(K=200\).

# For k=3

k <- 3

kMeans_result_k3 <- kmeans(imagemRGB[, c("R", "G", "B")], centers = k)

imagemRGB_k3 <- imagemRGB |>

mutate(cluster = kMeans_result_k3$cluster) |>

mutate(kColours = rgb(

kMeans_result_k3$centers[cluster, "R"],

kMeans_result_k3$centers[cluster, "G"],

kMeans_result_k3$centers[cluster, "B"]

))

# Plot for k=3

p2 <- ggplot(imagemRGB_k3, aes(x = X, y = Y, color = I(kColours))) +

geom_point(show.legend = FALSE, shape = 15, size = 0.1) +

labs(title = paste("K-Means (k =", k, "cores)")) +

theme_minimal() + theme(aspect.ratio = dim(imagem)[1]/dim(imagem)[2]) + scale_color_identity()R Example: K-Means on Image Pixels

K-Means with K=10 Colors

k <- 10

kMeans_result_k10 <- kmeans(imagemRGB[, c("R", "G", "B")], centers = k)

imagemRGB_k10 <- imagemRGB |>

mutate(cluster = kMeans_result_k10$cluster) |>

mutate(kColours = rgb(

kMeans_result_k10$centers[cluster, "R"],

kMeans_result_k10$centers[cluster, "G"],

kMeans_result_k10$centers[cluster, "B"]

))

p3 <- ggplot(imagemRGB_k10, aes(x = X, y = Y, color = I(kColours))) +

geom_point(show.legend = FALSE, shape = 15, size = 0.1) +

labs(title = paste("K-Means (k =", k, "cores)")) +

theme_minimal() + theme(aspect.ratio = dim(imagem)[1]/dim(imagem)[2]) + scale_color_identity()R Example: K-Means on Image Pixels

K-Means with K=200 Colors

k <- 200

kMeans_result_k200 <- kmeans(imagemRGB[, c("R", "G", "B")], centers = k)

imagemRGB_k200 <- imagemRGB |>

mutate(cluster = kMeans_result_k200$cluster) |>

mutate(kColours = rgb(

kMeans_result_k200$centers[cluster, "R"],

kMeans_result_k200$centers[cluster, "G"],

kMeans_result_k200$centers[cluster, "B"]

))

p4 <- ggplot(imagemRGB_k200, aes(x = X, y = Y, color = I(kColours))) +

geom_point(show.legend = FALSE, shape = 15, size = 0.1) +

labs(title = paste("K-Means (k =", k, "cores)")) +

theme_minimal() + theme(aspect.ratio = dim(imagem)[1]/dim(imagem)[2]) + scale_color_identity()R Example: K-Means on Image Pixels

K-Means with differents Colors

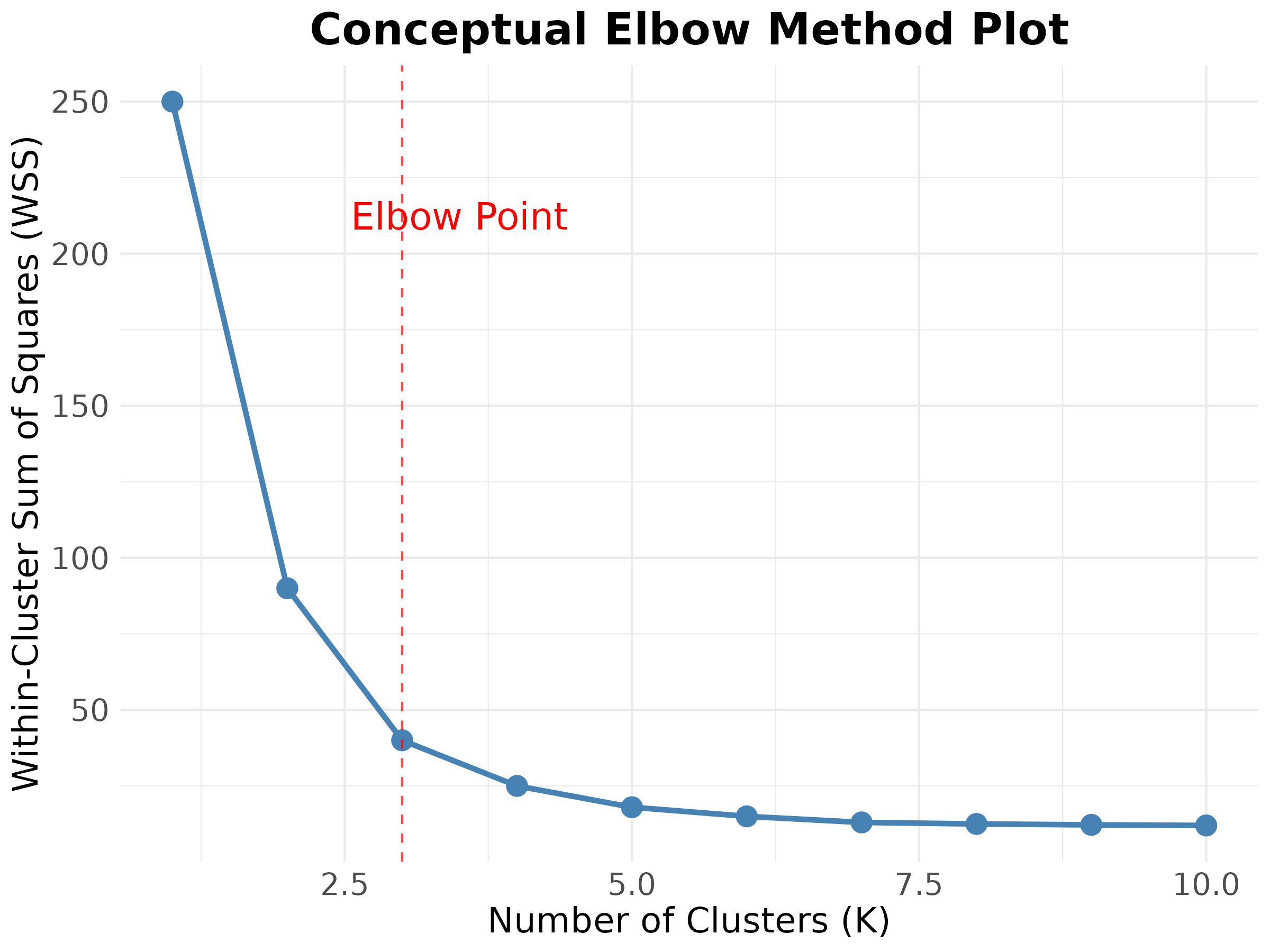

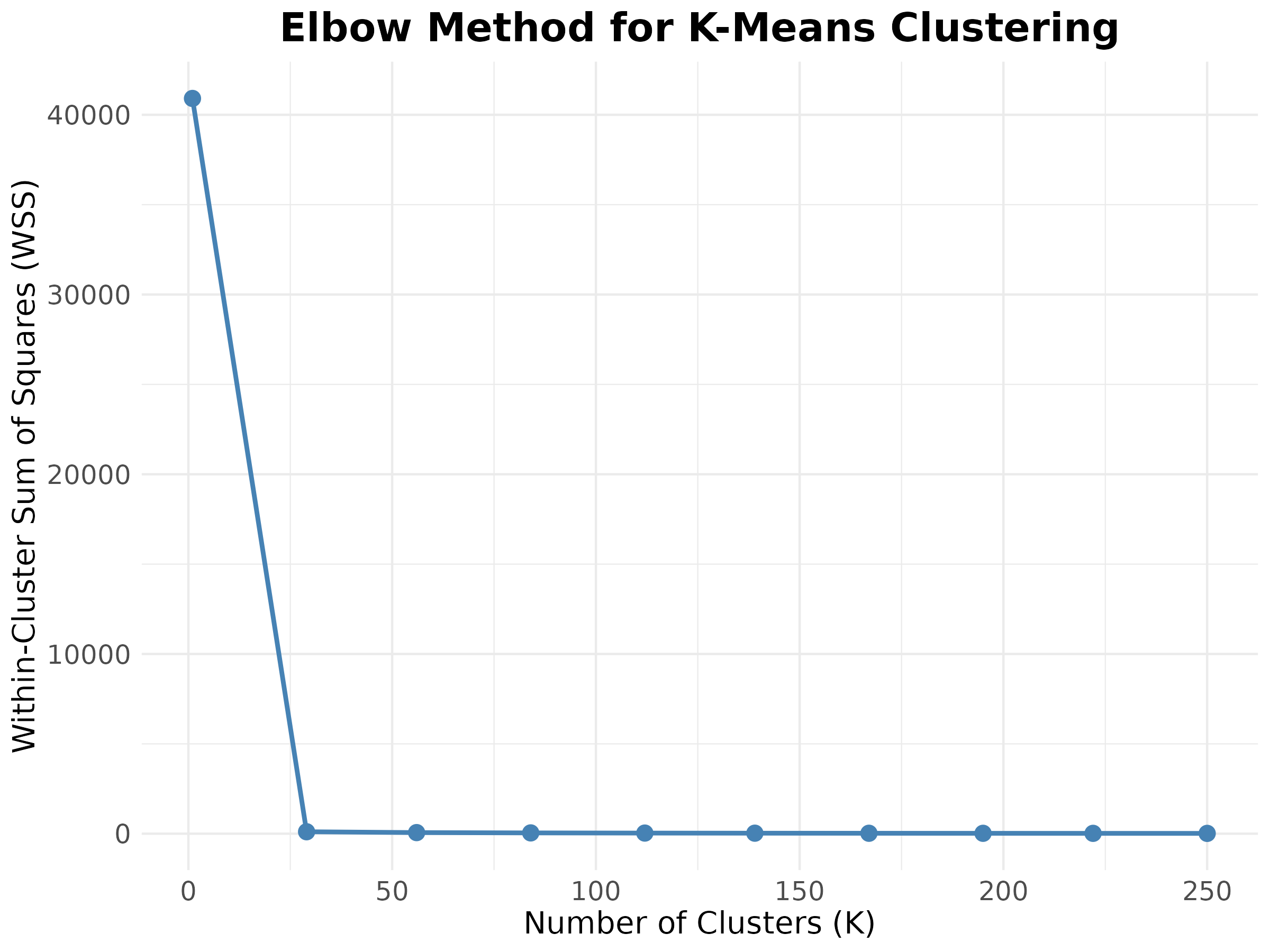

The Elbow Method

Defining the Optimal K

The Elbow method is a popular heuristic to help determine the optimal number of clusters (\(K\)) for the K-Means algorithm.

How it Works:

- It calculates the Within-Cluster Sum of Squares (WSS) for different values of \(K\) (e.g., from 1 to 10 or more).

- WSS measures the compactness of each cluster; the lower the WSS, the more compact the clusters.

- It then plots the WSS against \(K\).

The Elbow Method

Defining the Optimal K

Identifying the Ideal \(K\):

- As \(K\) increases, the WSS will always decrease (more clusters mean less dispersion within each).

- One looks for the point on the curve where the rate of decrease in WSS sharply changes and starts to ‘flatten out’ – this is the ‘elbow’.

- This point suggests that adding more clusters beyond this point does not provide a significant gain in the overall compactness of the clusters.

Considerations:

- It is a visual and subjective approach.

- A clear “elbow” may not always be apparent.

Example: Elbow Method

Practical Application - Jodavid Image

Example: Elbow Method

Practical Application - Jodavid Image

Hierarchical Clustering

Introduction

- One potential disadvantage of K-Means clustering is that it requires us to pre-specify the number of clusters K.

- Hierarchical clustering is an alternative approach which does not require that we commit to a particular choice of K.

- It results in an attractive tree-based representation of the observations, called a dendrogram.

Hierarchical Clustering

Agglomerative Approach

- This section describes bottom-up or agglomerative clustering.

- This is the most common type of hierarchical clustering.

- A dendrogram is generally depicted as an upside-down tree, built starting from the leaves and combining clusters up to the trunk.

Interpreting a Dendrogram

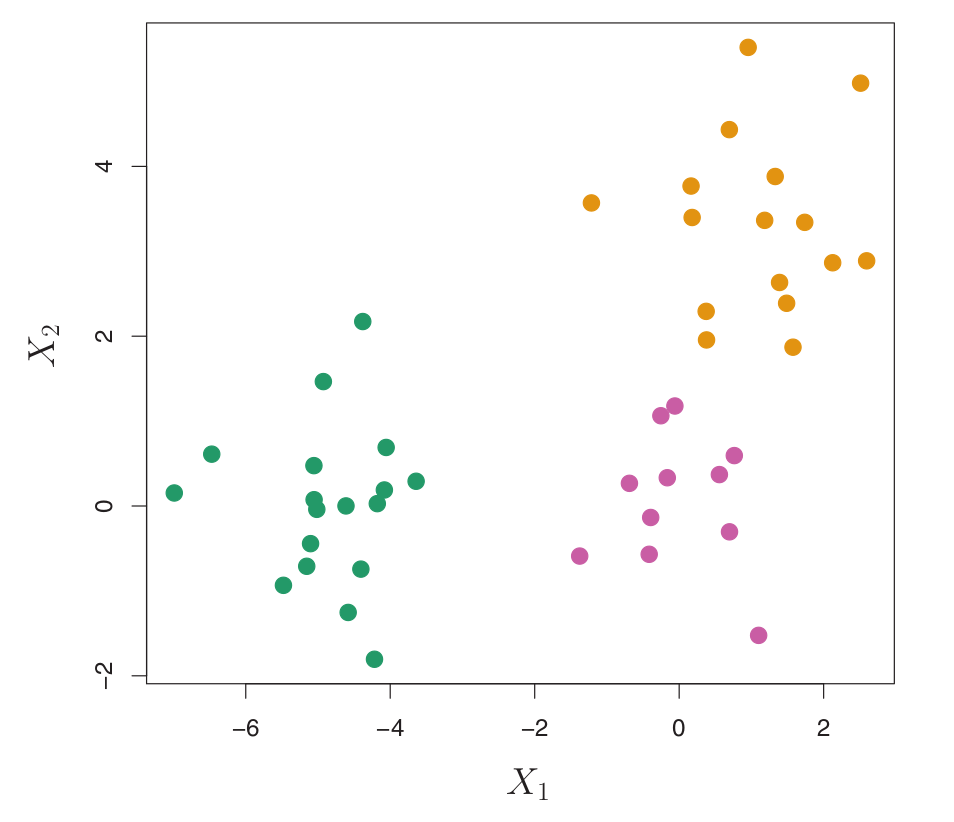

Example Data

- Consider a simulated data set with 45 observations in 2D space, generated from a three-class model.

- The true class labels are shown in different colors, but we will treat them as unknown for clustering.

Figure:

- 45 observations in 2D space.

- Three distinct classes, shown in separate colors.

- We will seek to cluster the observations to discover these classes.

Interpreting a Dendrogram

Fusions and Similarity

- In a dendrogram:

- Each leaf represents one observation.

- As we move up the tree, leaves fuse into branches. These fusions correspond to observations that are similar to each other.

- The earlier (lower in the tree) fusions occur, the more similar the groups of observations are to each other.

- Observations that fuse later (near the top of the tree) tend to be quite different.

- The height of this fusion (measured on the vertical axis) indicates how different the two observations/clusters are.

Interpreting a Dendrogram

Important Caution

- It is important to understand that the proximity of observations along the horizontal axis in a dendrogram does NOT imply similarity.

- For any two observations, similarity is determined by the height on the vertical axis where the branches containing those two observations first fuse.

- A dendrogram can be reordered horizontally without changing its meaning, as long as the vertical fusion heights are preserved.

Interpreting a Dendrogram

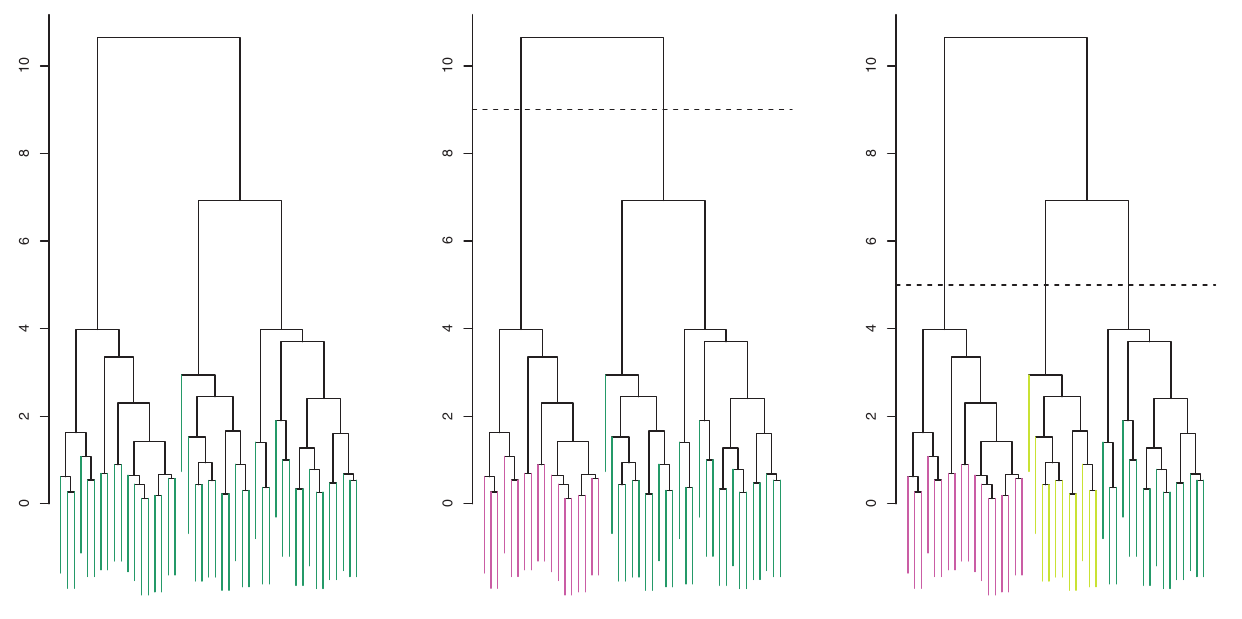

Identifying Clusters

- To identify clusters from a dendrogram, we make a horizontal cut across the tree.

- The distinct sets of observations beneath the cut can be interpreted as clusters.

- The height of the cut serves the same role as \(K\) in K-Means clustering: it controls the number of clusters obtained.

Figure:

- Left: Dendrogram.

- Center: Cut at height 9, yielding two clusters.

- Right: Cut at height 5, yielding three clusters.

- Colors are for display, not used in clustering.

Interpreting a Dendrogram

Identifying Clusters

Interpreting a Dendrogram

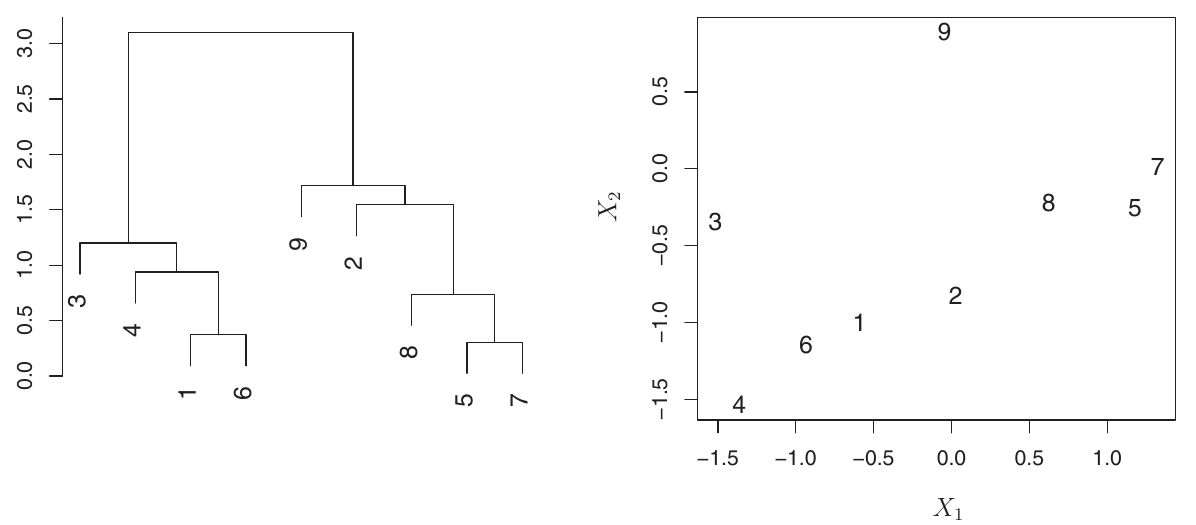

Horizontal Axis Caution Example

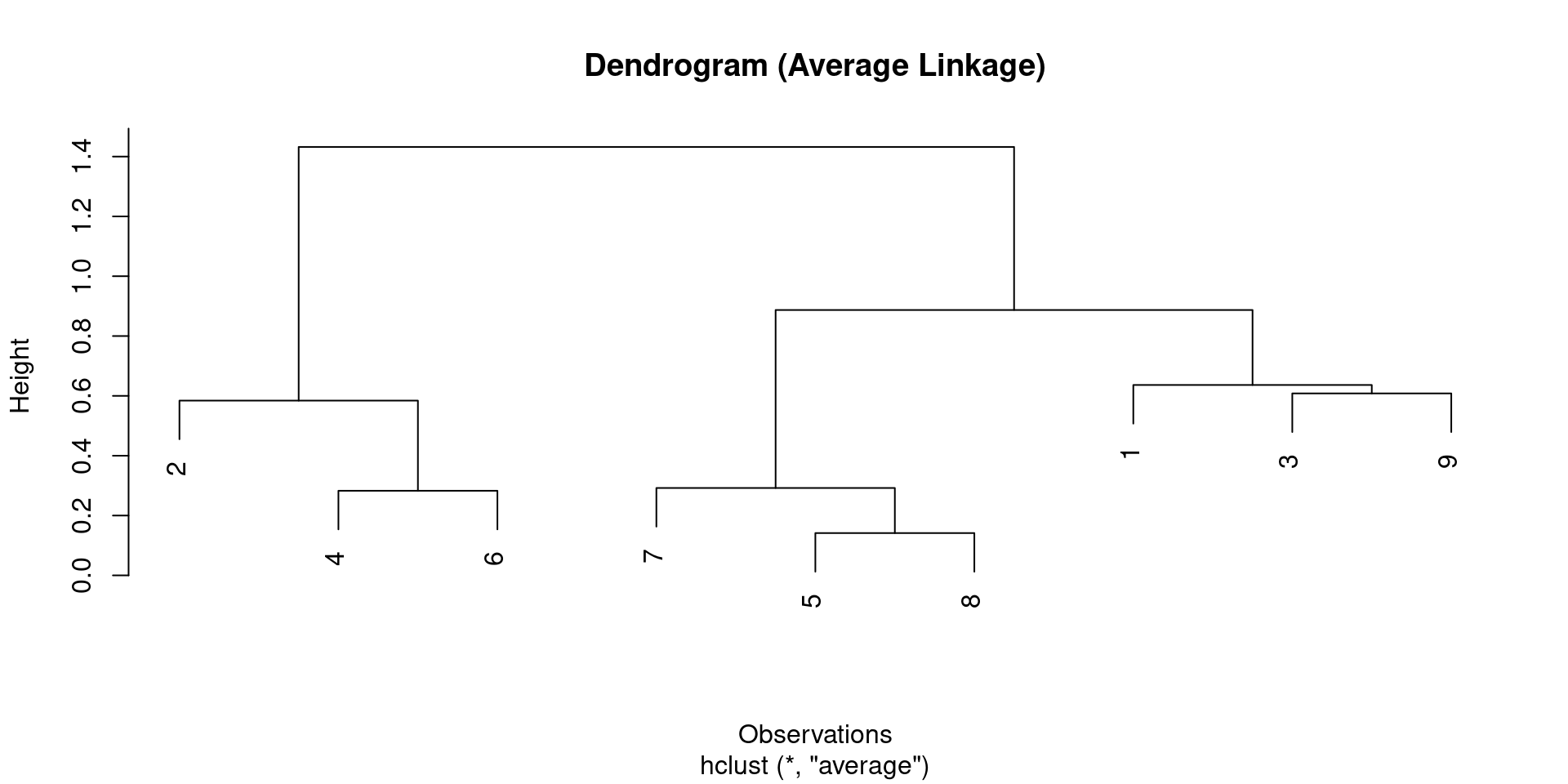

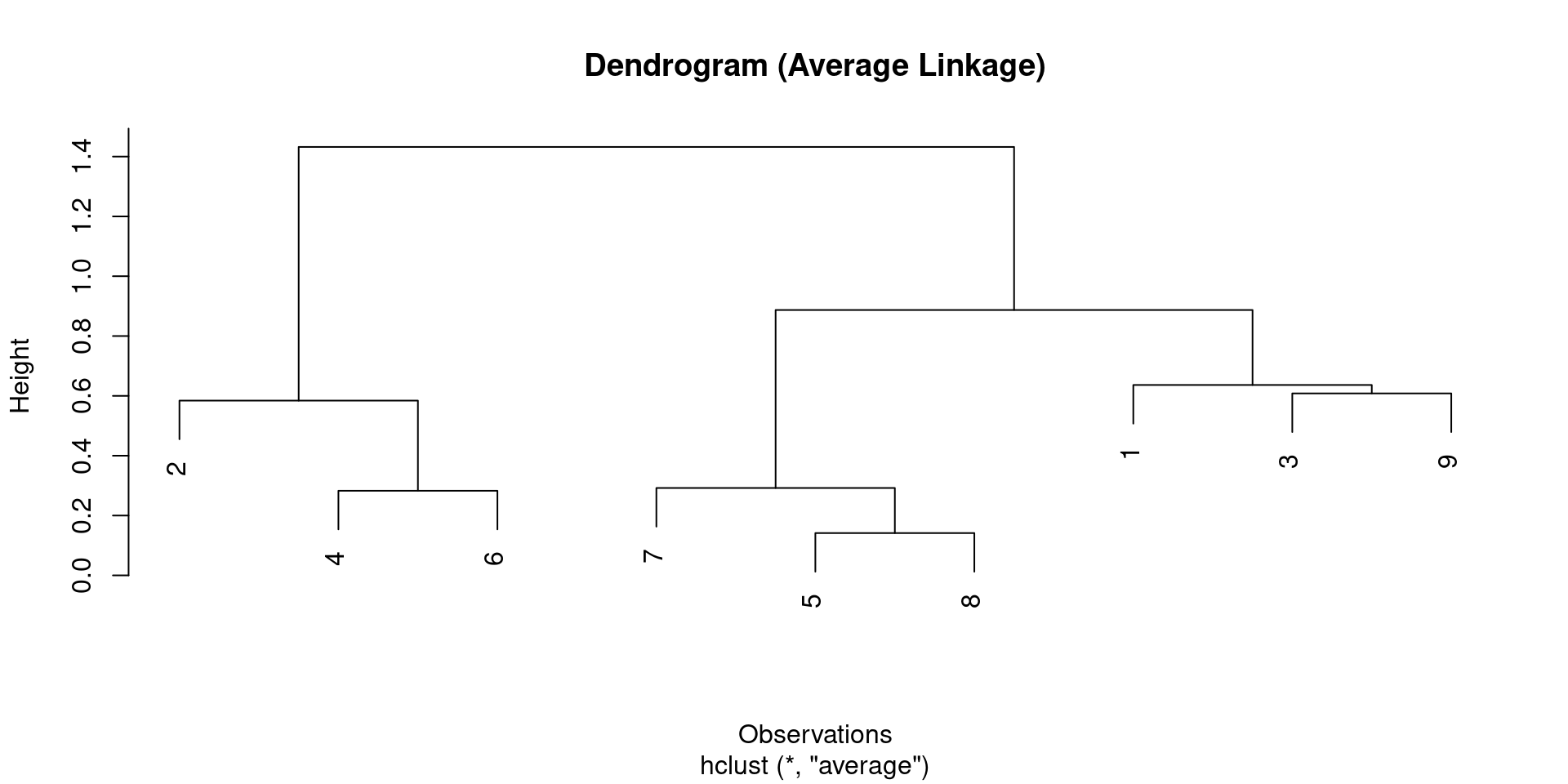

- Consider this dendrogram for 9 observations.

- Observations 5 and 7 are very similar (fuse low). Observations 1 and 6 are also similar.

- However, observations 9 and 2 are not necessarily similar just because they appear close horizontally. Their fusion height is higher.

Figure:

- Left: Dendrogram with 9 observations.

- Right: Raw data for these 9 observations.

- Confirms that horizontal proximity is misleading; vertical fusion height determines similarity.

The Hierarchical Clustering Algorithm

Steps

- The dendrogram is obtained via an extremely simple algorithm:

Initialize: Begin with \(n\) observations, treating each as its own cluster. Compute all \(\binom{n}{2} = n(n-1)/2\) pairwise dissimilarities (e.g., Euclidean distance).

Iterate (from \(i=n\) down to \(i=2\) clusters):

- Find Most Similar: Examine all pairwise inter-cluster dissimilarities among the \(i\) current clusters and identify the pair that are least dissimilar (most similar).

- Fuse Clusters: Fuse these two clusters into a single new cluster. The dissimilarity between these two clusters indicates the height in the dendrogram at which the fusion should be placed.

- Update Dissimilarities: Compute the new pairwise inter-cluster dissimilarities among the \(i-1\) remaining clusters (including the newly formed cluster).

Hierarchical Clustering

Dissimilarity Between Clusters (Linkage)

- The algorithm requires defining how to measure the dissimilarity between two clusters if one or both contain multiple observations.

- This is achieved by developing the notion of linkage, which defines the dissimilarity between two groups of observations.

Hierarchical Clustering

Linkage Types

- The four most common types of linkage are:

- Complete Linkage: Maximal inter-cluster dissimilarity. Compute all pairwise dissimilarities between observations in cluster A and cluster B, and record the largest of these dissimilarities.

- Single Linkage: Minimal inter-cluster dissimilarity. Compute all pairwise dissimilarities between observations in cluster A and cluster B, and record the smallest of these dissimilarities. Can result in extended, trailing clusters.

- Average Linkage: Mean inter-cluster dissimilarity. Compute all pairwise dissimilarities between observations in cluster A and cluster B, and record the average of these dissimilarities.

- Centroid Linkage: Dissimilarity between the centroid (mean vector) for cluster A and the centroid for cluster B. Can result in undesirable inversions.

Hierarchical Clustering

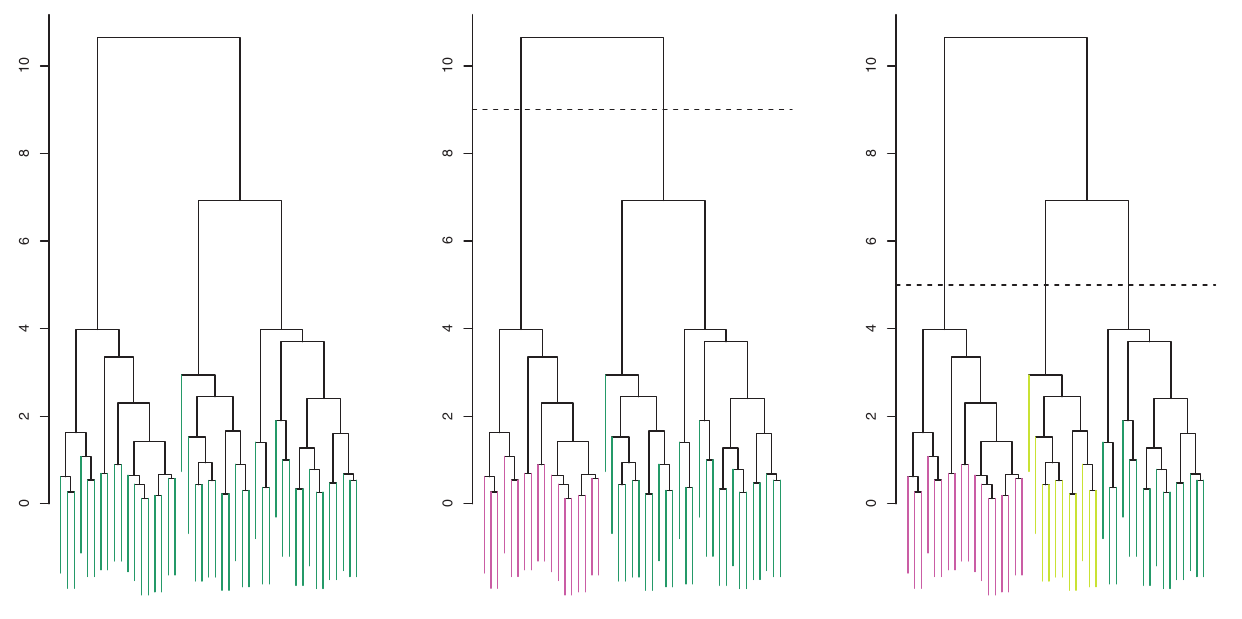

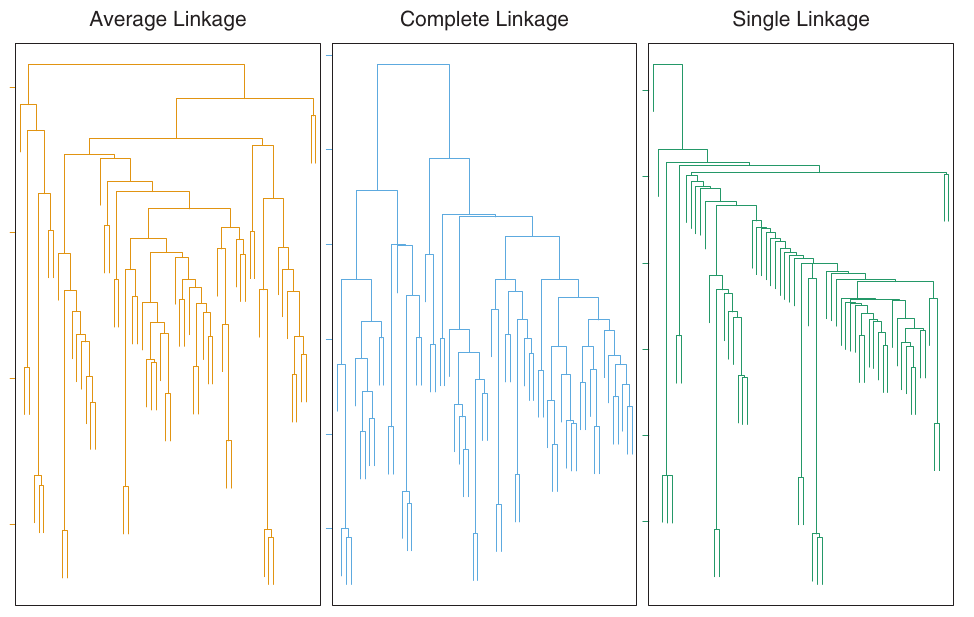

Linkage Type Impact

- Average, complete, and single linkage are most popular.

- Average and complete linkage are generally preferred as they tend to yield more balanced dendrograms.

- Centroid linkage can suffer from an inversion, where two clusters are fused at a height below either of the individual clusters in the dendrogram. This can hinder visualization and interpretation.

Figure:

- Shows how different linkage methods (Average, Complete, Single) applied to the same dataset produce different dendrogram structures.

- Average and Complete linkage tend to yield more balanced clusters.

Choice of Dissimilarity Measure

Euclidean vs. Correlation-based

- Euclidean distance is commonly used.

- However, other dissimilarity measures might be preferred depending on the application.

- Correlation-based distance considers two observations similar if their features are highly correlated, even if their observed values are far apart in terms of Euclidean distance.

- This is an “unusual” use of correlation, normally computed between variables. Here, it’s computed between observation profiles.

- Focuses on the shapes of observation profiles rather than their magnitudes.

Choice of Dissimilarity Measure

Example: Shopping Data

- Consider an online retailer clustering shoppers based on purchase histories (items purchased).

- If Euclidean distance is used, shoppers who bought very few items overall (infrequent users) might be clustered together, regardless of what they bought. This might not be desirable.

- If correlation-based distance is used, shoppers with similar preferences (e.g., bought items A and B but never C or D) will be clustered together, even if some shoppers are high-volume and others low-volume. This might be a better choice for understanding preferences.

Choice of Dissimilarity Measure

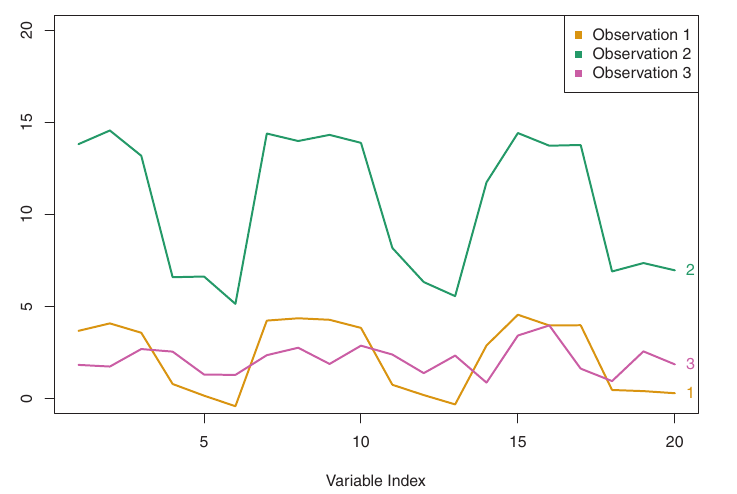

Illustration

Figure:

- Three observations with 20 variables.

- Obs 1 & 3: Similar values, small Euclidean distance, weakly correlated, large correlation-based distance.

- Obs 1 & 2: Different values, large Euclidean distance, highly correlated, small correlation-based distance.

Scaling Variables

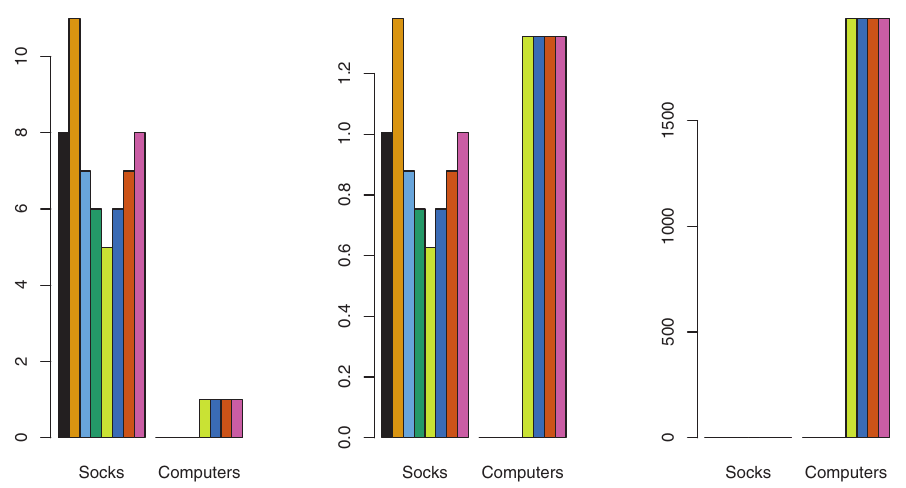

Importance

- Another crucial consideration: Should variables be scaled to have standard deviation one before computing dissimilarity?

- Example: Online Shopping (Socks vs. Computers)

- A shopper buys 10 pairs of socks/year, but a computer rarely.

- If raw values are used: Socks purchases (high frequency) will have a much larger effect on dissimilarities than computer purchases (low frequency).

- This might be undesirable if the goal is to identify preference patterns for more valuable items like computers.

Scaling Variables

Illustration

If variables are scaled to have standard deviation one, each variable is given equal importance.

Also important when variables are measured on different scales (e.g., centimeters vs. kilometers). The choice of units can greatly affect the dissimilarity measure.

Figure:

- Left: Raw purchases (socks dominate).

- Center: Purchases scaled by standard deviation (computers now have greater relative effect).

- Right: Dollars spent (computers clearly dominate due to price).

- Clustering results will differ significantly based on these choices.

R Example: Hierarchical Clustering

Synthetic Data for Demonstration

- We will generate a small synthetic dataset to demonstrate hierarchical clustering, similar to the one in the Portuguese PDF.

- This data will consist of 9 points in 2D space.

# A tibble: 9 × 3

id X1 X2

<int> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 0.1 0.4

2 2 -0.2 -0.3

3 3 0.5 0.9

4 4 -0.8 -0.7

5 5 0.7 0.1

6 6 -0.6 -0.5

7 7 0.8 0.3

8 8 0.6 0

9 9 -0.1 1 R Example: Hierarchical Clustering

Code - Hierarchical Clustering

- We will use

hclustfor hierarchical clustering andcutreeto obtain clusters. dist()calculates the distance matrix.

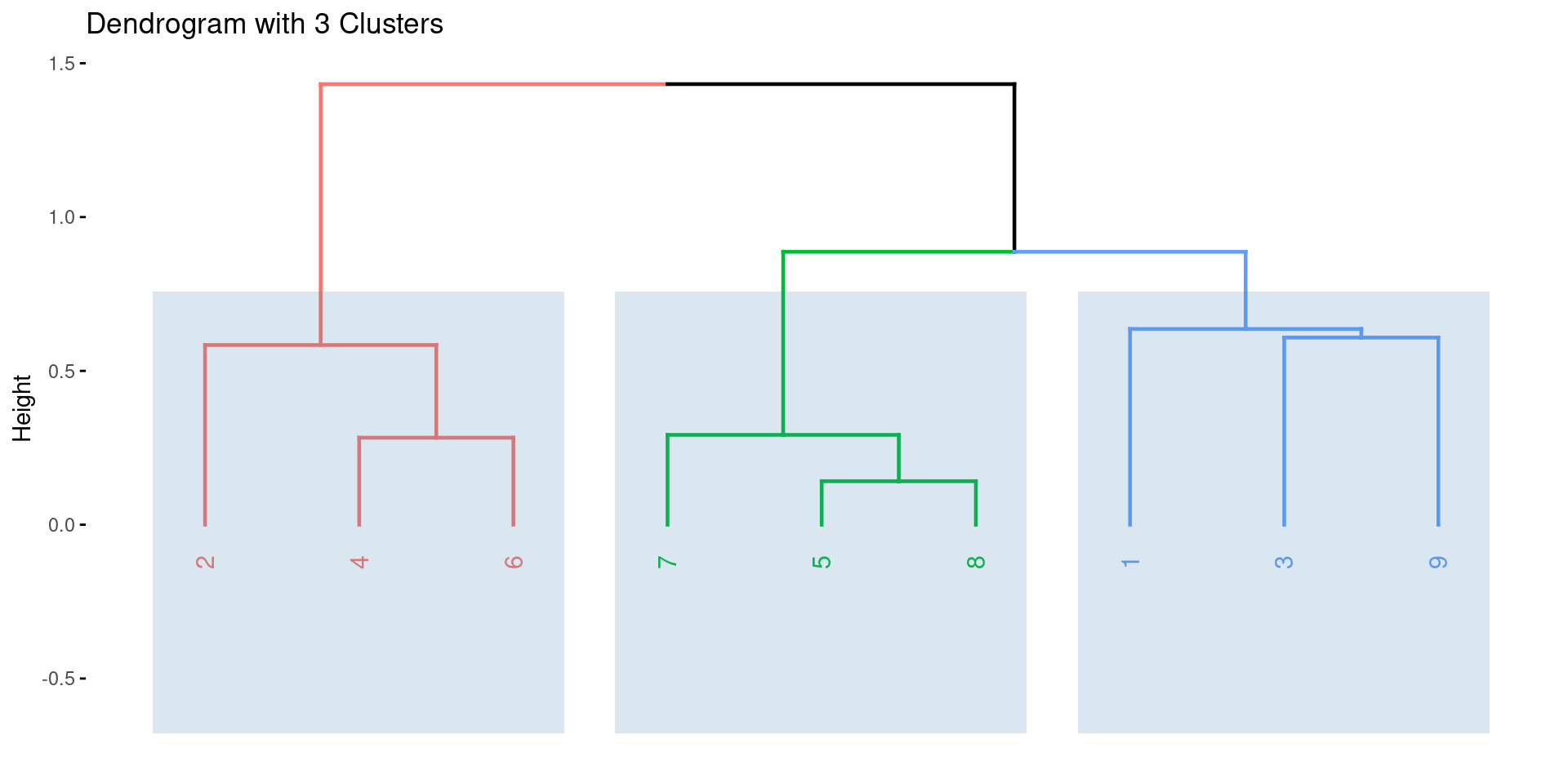

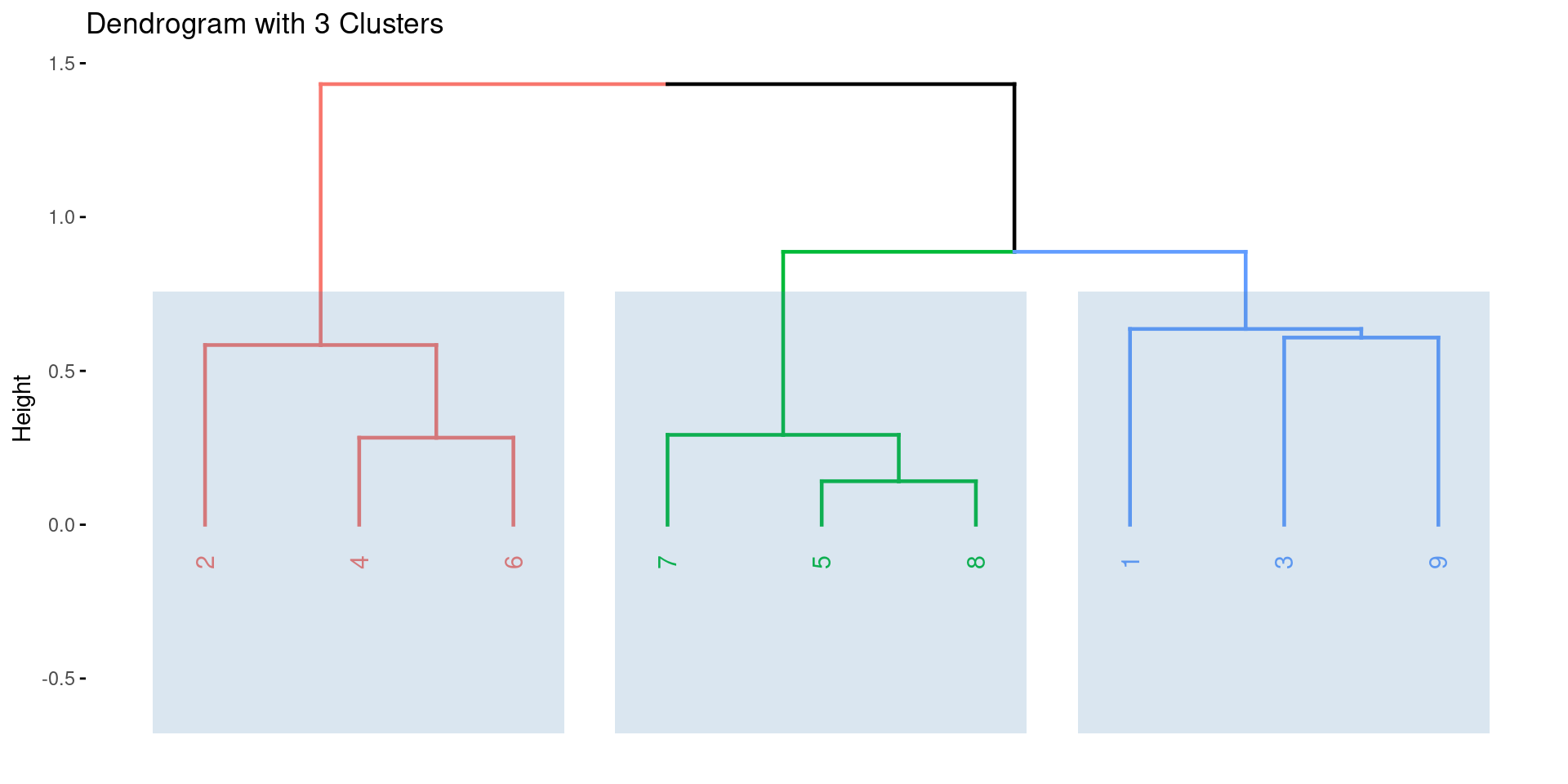

# A tibble: 9 × 4

id X1 X2 cluster_h

<int> <dbl> <dbl> <int>

1 1 0.1 0.4 1

2 2 -0.2 -0.3 2

3 3 0.5 0.9 1

4 4 -0.8 -0.7 2

5 5 0.7 0.1 3

6 6 -0.6 -0.5 2

7 7 0.8 0.3 3

8 8 0.6 0 3

9 9 -0.1 1 1

R Example: Hierarchical Clustering

Dendrogram Visualization

- The plot generated by

plot(dendrograma)is the standard R dendrogram.

R Example: Hierarchical Clustering

Enhanced Visualization with factoextra

- The

factoextrapackage provides excellent tools for visualizing clustering results, including dendrograms with enhanced features.

R Example: Hierarchical Clustering

Dendrogram with 3 Clusters

Practical Issues in Clustering

Small Decisions with Big Consequences

- When performing clustering, several decisions must be made, which can strongly impact the results:

- Data Standardization: Should observations or features be standardized (e.g., centered to mean zero, scaled to standard deviation one)?

- Dissimilarity Measure (Hierarchical): What dissimilarity measure should be used (e.g., Euclidean, correlation-based)?

- Linkage Type (Hierarchical): What type of linkage should be used (e.g., complete, average, single)?

- Number of Clusters (K-Means & Hierarchical): How many clusters should be sought (\(K\) for K-Means, or where to cut the dendrogram)?

Practical Issues in Clustering

Validating the Clusters Obtained

- Any clustering method will produce clusters. The critical question is: Do these clusters represent true subgroups in the data, or are they simply a result of clustering the noise?

- Robustness: If we cluster the data again after removing a random subset of observations, would we obtain similar clusters? Often, this is not the case, indicating sensitivity to perturbations.

- P-values: Techniques exist to assign a p-value to a cluster, assessing whether there is more evidence for the cluster than expected by chance. However, there is no consensus on a single best approach.

Practical Issues in Clustering

Other Considerations

- Both K-Means and hierarchical clustering force every observation into a cluster.

- This might be inappropriate if some observations are outliers that do not truly belong to any subgroup.

- Mixture models are an attractive approach that can accommodate outliers and offer a “soft” version of K-Means clustering, where observations can belong to multiple clusters with certain probabilities.

Final Thoughts

- Clustering is a powerful tool for discovering hidden structures in unlabeled data.

- Choosing the right clustering method, dissimilarity measure, linkage type, and number of clusters is crucial and often application-specific.

- Careful validation and consideration of practical issues like outliers and data perturbations are essential for meaningful results.

References

Basics

Aprendizado de Máquina: uma abordagem estatística, Izibicki, R. and Santos, T. M., 2020, link: https://rafaelizbicki.com/AME.pdf.

An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R, James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. and Tibshirani, R., Springer, 2013, link: https://www.statlearning.com/.

Mathematics for Machine Learning, Deisenroth, M. P., Faisal. A. F., Ong, C. S., Cambridge University Press, 2020, link: https://mml-book.com.

References

Complementaries

An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in python, James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. and Tibshirani, R., Taylor, J., Springer, 2023, link: https://www.statlearning.com/.

Matrix Calculus (for Machine Learning and Beyond), Paige Bright, Alan Edelman, Steven G. Johnson, 2025, link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.14787.

Machine Learning Beyond Point Predictions: Uncertainty Quantification, Izibicki, R., 2025, link: https://rafaelizbicki.com/UQ4ML.pdf.

Mathematics of Machine Learning, Petersen, P. C., 2022, link: http://www.pc-petersen.eu/ML_Lecture.pdf.

Statistical Machine Learning - Prof. Jodavid Ferreira